Baseline Design System

Introduction

Baseline started as a simple enough brief: create a sample design system that zeroheight could use for demos. But a basic starter kit wasn’t going to cut it. To be genuinely useful, it needed to reflect the reality of what our customers are building: large-scale, enterprise-level systems with multi-brand architectures, complex component libraries, and proper token pipelines feeding real code.

So that’s what I built. Baseline is a fictional fintech SaaS company with three distinct brands, over 1,000 component variants, a fully automated design-to-code token pipeline, a React component library published to NPM, and comprehensive documentation covering everything from accessibility guidelines to UX patterns. It’s a design system that could ship a real product. And I built it in three weeks.

This case study walks through how I approached the project: establishing the foundational architecture, designing a scalable component library, solving workflow problems with custom tooling, packaging everything for developers, and documenting it all in a way that’s useful for both humans and AI.

Establishing the foundations

Before touching a single component, I needed to establish what this system was actually for. The brief was clear: create a design system that mirrors what zeroheight sees across our customer base: large enterprise tech companies, typically running multi-brand setups with all the complexity that entails. This wasn’t going to be a simple starter kit. It needed to feel real, with the kind of architectural decisions that only emerge when you’re designing for scale.

I landed on a fictional fintech SaaS company as the foundation, which gave me room to create three distinct brands under one umbrella. Baseline is the core product brand. Clean, professional, the workhorse. Baseline Pro is a premium tier within that core offering, sharing DNA but with its own elevated personality. And then there’s Offset, a consumer-facing payments brand that needed to feel approachable and, for lack of a better word, fuzzier than its siblings. Three brands, one system, plenty of opportunities to stress-test the architecture.

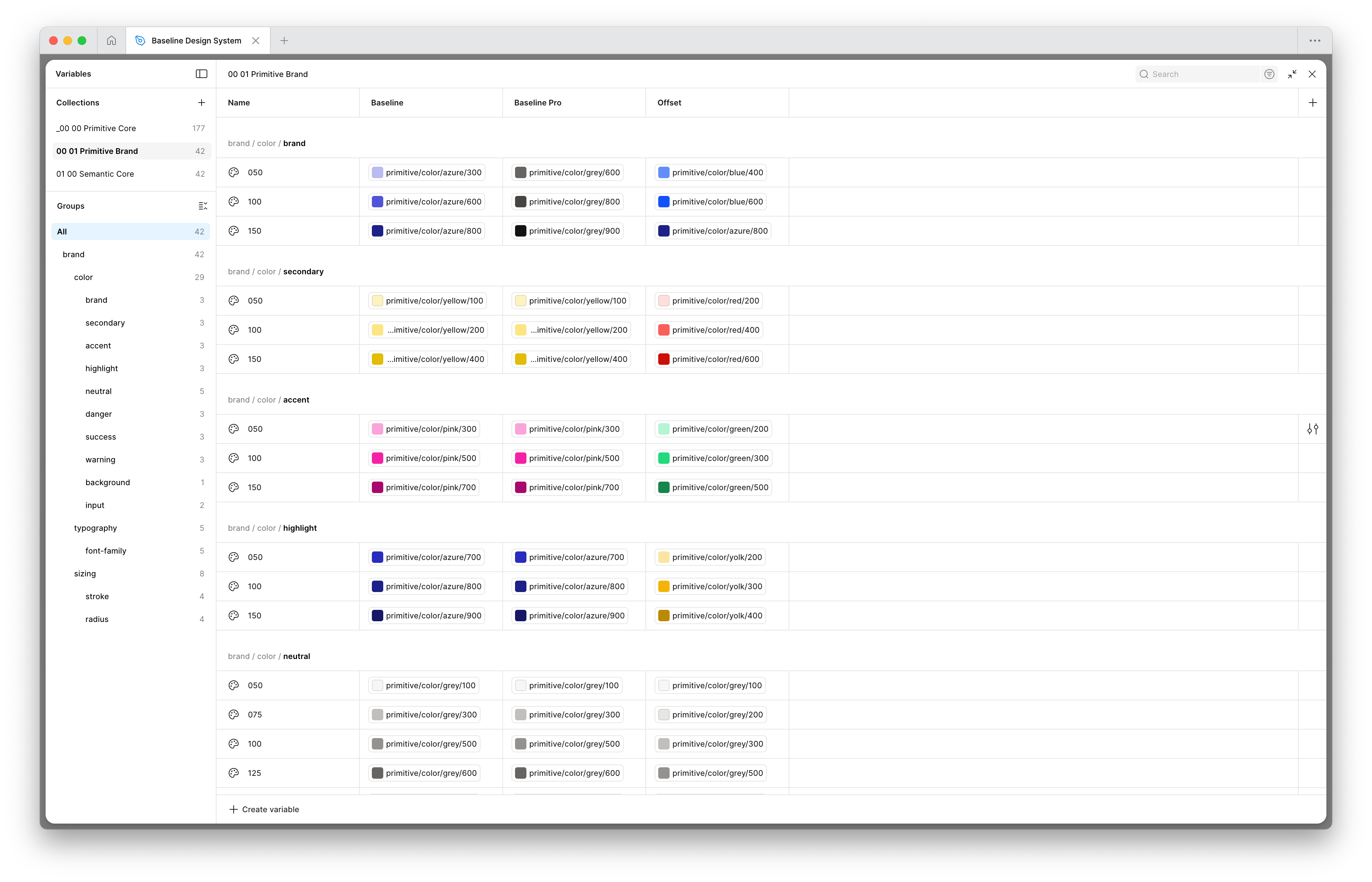

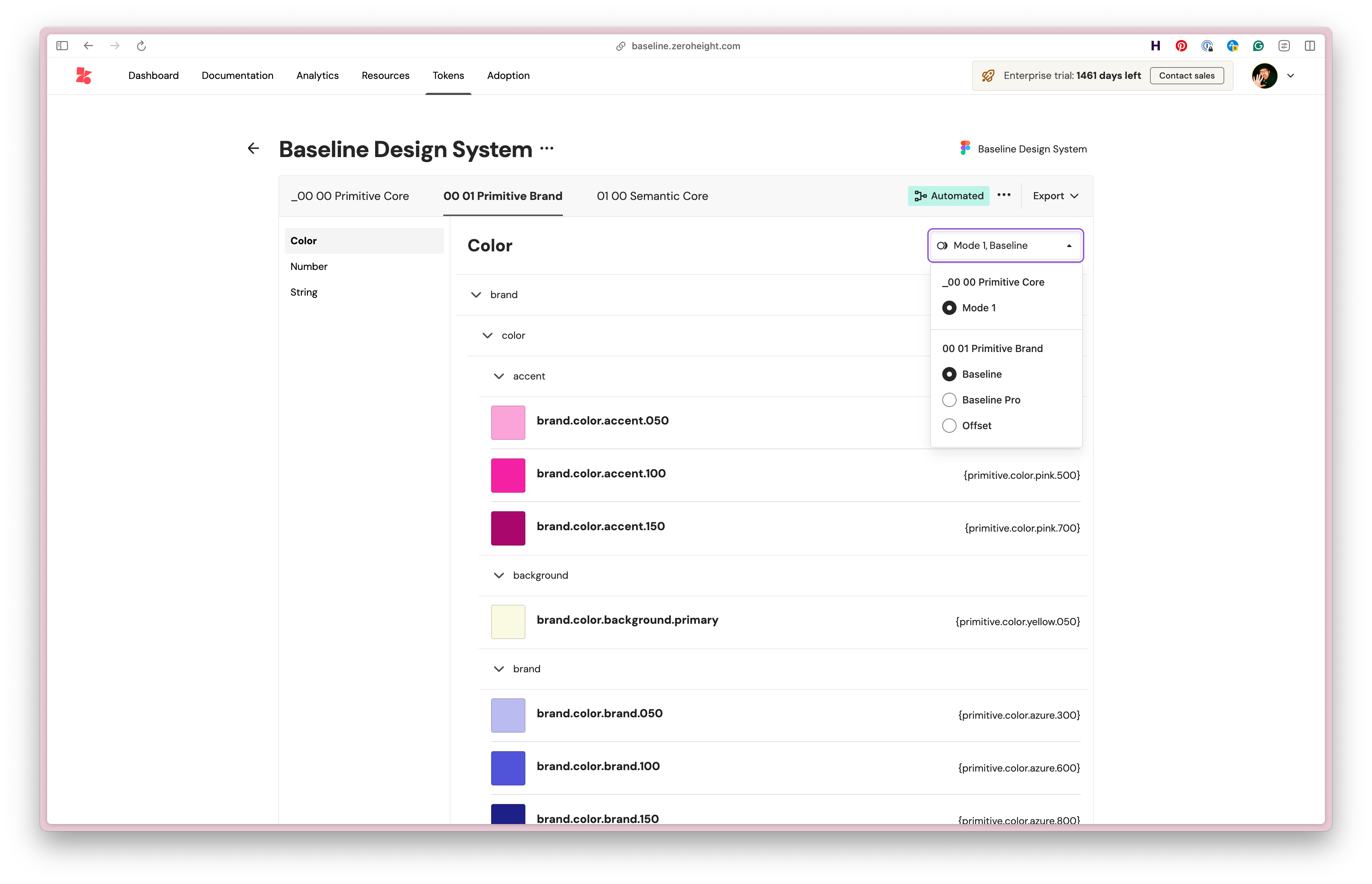

The variable setup in Figma was where the real groundwork happened. I built out a three-tier token architecture – comprising primitive, semantic, and component layers – with brand theming handled via modes at the semantic level. This means any component can switch between Baseline, Baseline Pro, or Offset with a mode change, inheriting the right colours, typography, and spacing without any manual overrides. It needed to be scalable, but more importantly, it needed to demonstrate best practice for how teams should actually structure their variables.

With the architecture in place, I worked through all the standard brand elements you’d expect from a real-world system: colour palettes, typography scales, spacing and sizing tokens, and a full icon set. I also built out the practical stuff that often gets overlooked in sample systems: logos, imagery guidelines, and landing pages that show how everything comes together in context.

Semantic variables in Figma. I laid out the foundation of the design system in a three-tier architecture, with brand theming handled via modes at the semantic level.

The variables are pulled in dynamically to zeroheight to convert to design tokens, so they can be used in Style Dictionary.

Designing the system

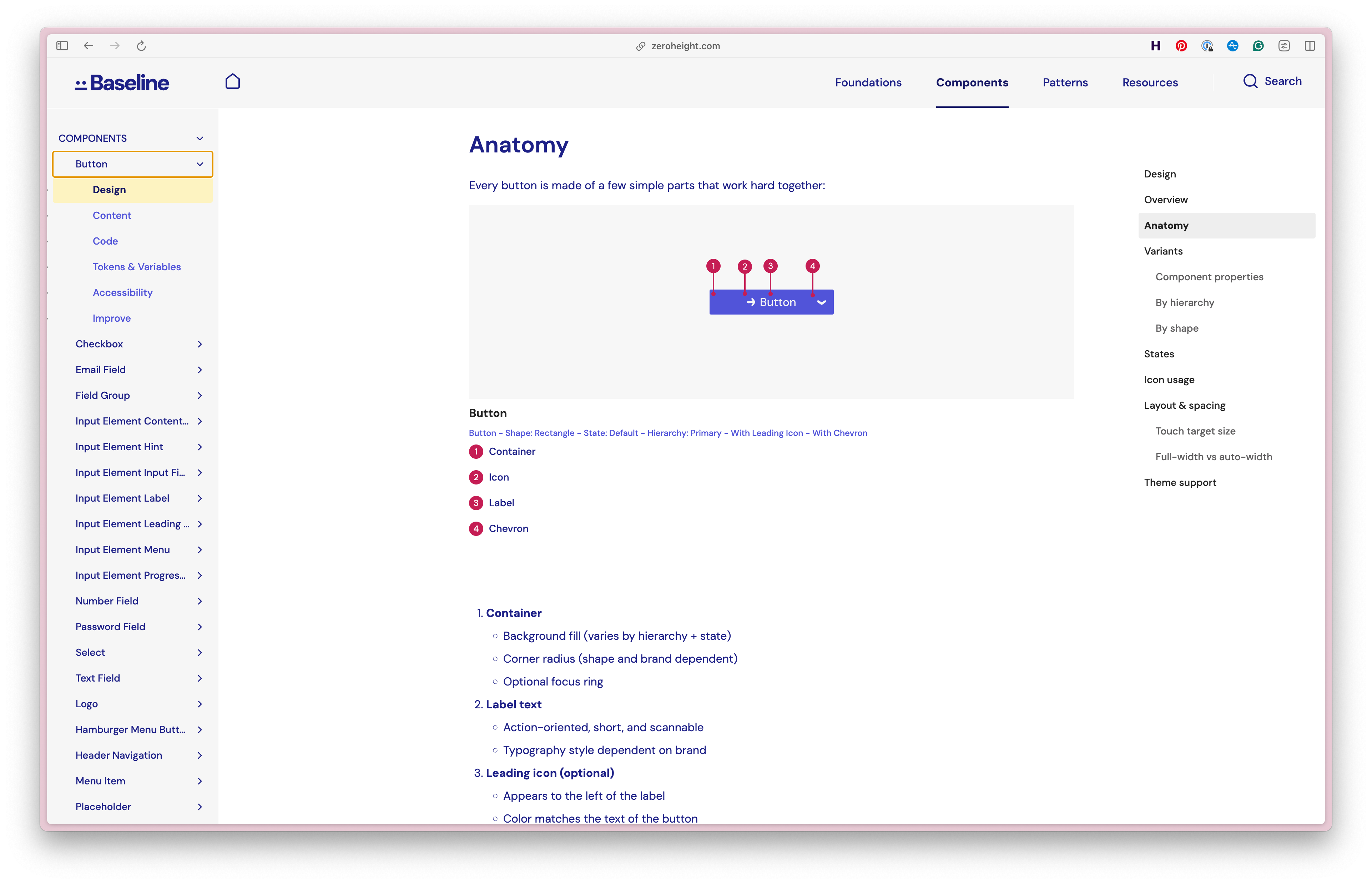

With the foundations in place, I moved on to building out the component library itself. The goal was to create a full set of components you’d typically expect in a SaaS product: buttons, inputs, navigation, switches, steppers, sliders, the works. Nothing revolutionary in terms of what’s included, but the ambition was in how they were built.

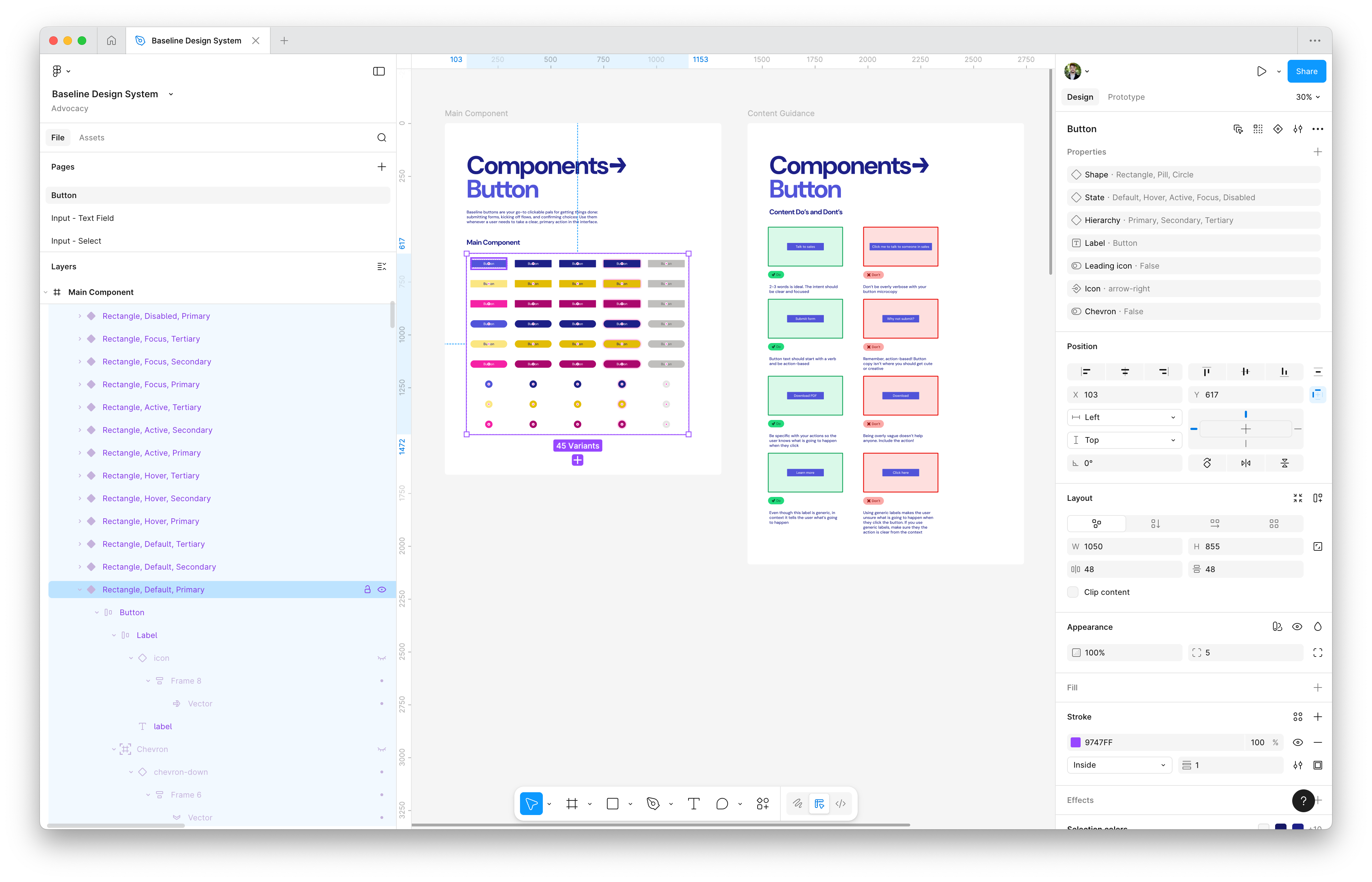

Rather than creating the simplest possible version of each component, I wanted to mirror the complexity I’ve encountered building components in the real world. That meant breaking everything down into its atomic pieces and building back up from there, with smart options exposed as props so each component could flex to cover a wide range of use cases. A button isn’t just a button. It’s a considered system of sizes, states, icon positions, and variants that all need to work together without falling apart. By the end, the library contained over 10,000 different component variants.

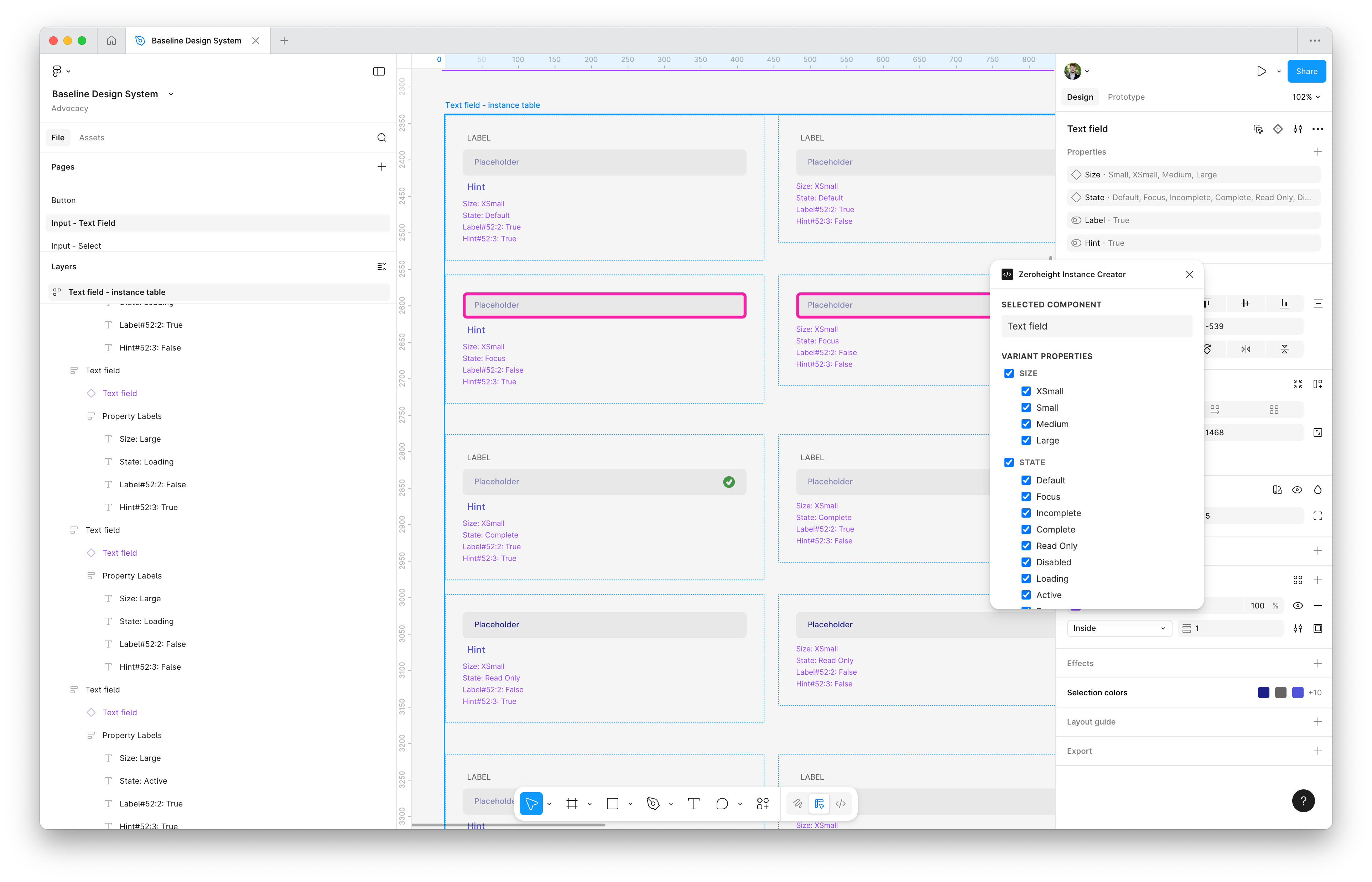

The text input is a good example of this approach in action. What looks like a single component is actually a carefully orchestrated set of elements: labels, hints, icons, validation states, character counts, all wired up so you can toggle options on and off without breaking the underlying structure. It’s the kind of complexity that’s invisible when it’s working well, but falls apart quickly if you cut corners.

I also knew from the start that this system would be used to demonstrate zeroheight’s Figma MCP alongside our own MCP, showing how AI tools like Cursor can generate interfaces from well-structured design systems. That meant everything needed to be rigorously tokenised and thoroughly documented. If the tokens are messy or the naming is inconsistent, the AI output suffers, so this became a forcing function for maintaining quality throughout.

The Button component in the Figma library, with variants and booleans to control the variations on the component. I also include paired down guidance that's important for designers when using the component.

Finding and fixing the problems

Building a system of this scale inevitably surfaces friction. Small annoyances that you can ignore on a simple project become genuine blockers when you’re repeating the same task dozens of times. Rather than just pushing through, I decided to solve a couple of these problems properly by building small, focused Figma plugins.

The first issue was creating variables for the colour ramps I’d established for each brand. Converting colours from the canvas into properly structured variable collections is tedious, repetitive work. There are existing plugins in the community that help with this, but none of them handled the specific workflow I needed. So I built my own. It’s a simple tool, but it saved a couple of hours of manual work and is now being kept internal as a utility for the zeroheight team.

The second problem came from how I was using boolean properties to control component variants. I needed a way to visualise all the possible combinations as instances on the canvas, and crucially, to name and format them correctly so they’d import cleanly into zeroheight. Again, there were community options available, but nothing quite satisfied the requirements. This plugin had a bigger impact: it saved me one to two days of manually creating and naming component instances. Unlike the first, I’ve published this one to the Figma community, where it’s currently working its way through the approval process.

The zeroheight Instance Creator takes all of the variants and boolean properties on a component and creates a new instance for each combination.

I created the simple plugin using the Figma API and JavaScript.

Packaging up for delivery

A design system only really proves itself when it’s running in code. The Figma library was comprehensive, but it needed a production-ready counterpart to demonstrate the full value of what we’d built.

The first step was establishing a variable-to-token pipeline using zeroheight and Style Dictionary. The goal was a fully automated process: variables defined in Figma would be translated into tokens in zeroheight, then transformed via Style Dictionary into CSS variables ready for use in real components. This meant getting into the weeds of Style Dictionary transforms and building custom scripts on top of the standard tooling to make sure the output made sense to developers. Token pipelines can get messy quickly, so I wanted this to be a clear, replicable example of how to do it well.

From there, I built out all the components as React components, packaging everything up as an NPM package that could be served to consumers. These needed to be properly architected, functional components with real interactivity, not just styled rectangles ported from Figma. The kind of thing a developer could actually drop into a project and use.

To surface all of this, I created a Storybook instance that documents every component and its available props, complete with working interactions. I also built in a brand switcher that lets you toggle between Baseline, Baseline Pro, and Offset, demonstrating the token architecture in action. Switch brands, and the entire component library updates to match.

Finally, I created Code Connect files for every component. This ties the Figma components directly to their code counterparts, which becomes essential when using the Figma MCP to generate sample screens. The AI knows exactly which component to reach for and how to use it.

The Github repo includes the NPM package, the Storybook instance, and the Code Connect files for each component.

The Storybook shows the components in action, with working examples and props for each variant.

Documenting the design system

With the design and code work complete, the final stage was bringing it all together in zeroheight. This was an opportunity to showcase as many platform features as possible: theming, design blocks, token blocks, component sets, status tables, and more. But beyond feature coverage, I wanted to demonstrate a thorough approach to component documentation that would prove its value when connected to the zeroheight MCP.

Each component documentation page follows a consistent structure. Design guidelines cover the visual and interaction principles. Content guidelines address the language and tone for labels, hints, and error messages. The code section surfaces the React implementation with working examples. Token usage explains which tokens are in play and how they map to the component’s visual properties. Accessibility guidelines document keyboard interactions, ARIA requirements, and any specific considerations for assistive technology. Finally, a feedback section provides a channel for questions and improvements.

This structure isn’t arbitrary. When an AI tool queries the MCP to understand how to use a component, it needs more than just a prop list. It needs context: when to use the component, how to write for it, what accessibility requirements apply. The documentation becomes part of the system’s intelligence.

Beyond component pages, I also created a set of sample UX patterns, a section that’s often overlooked in design systems but invaluable for showing how components combine to solve real problems. Extensive foundational guidelines round out the documentation, covering everything from colour and typography to spacing and iconography.

The zeroheight cover page for the design system, with custom imagery to make it feel more like a real product.

The zeroheight documentation page for the design system, showing guidance for design and content, as well as the code and token usage for each component.

Conclusion

Baseline ended up being a much larger project than I initially anticipated, but that scope was the point. A sample system is only valuable if it demonstrates real complexity, and real complexity forces you to make the same hard decisions your customers are making every day. The three-week timeline kept things focused: every decision had to earn its place.

Building this gave me a deeper appreciation for the full lifecycle of a design system: the architectural choices that either scale gracefully or become painful, the tooling gaps that slow teams down, and the documentation that transforms a component library into something people can actually use. It also gave zeroheight a genuinely robust demo environment and a foundation for showcasing what’s possible when design systems are built with care.

The system continues to evolve, but at its core, Baseline is proof that doing things properly pays off, even when the brief would let you get away with less.